“A.J. began to change, going from outgoing and bubbly to pulling into his shell,” said veteran NFL player Doug Middleton of his childhood best friend. “He stopped wanting to be social. He stopped showering.” Middleton and Anthony “A.J.” Morrison, Jr., had been best friends since they were six. They were like brothers.

The boys grew up on the same street in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, and supported each other as they developed as athletes—Middleton played football, and A.J. ran track. “We were just looking to chase our dreams and make it professionally, and we continued to work on that together,” he reminisced. When the New York Jets signed Middleton in 2016, A.J. was there to support and celebrate with him.

By then, Middleton had already noticed changes in his best friend. His mother is a therapist, so he wasn’t a total stranger to mental health challenges. “My mom was my first entry point into learning about mental health and what she did on a daily basis to help others,” he said. He knew people suffered from anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder. “It’s a lot different seeing your best friend battle and trying to fight through it.”

As A.J.’s mental health deteriorated, Middleton witnessed the seemingly endless barriers in his friend’s way as a young Black man, including stigma and insufficient access to resources. Desperate to help, Middleton said he didn’t realize it could take a while to find the right therapist and the right medication. A.J. struggled with the adverse side effect of the medication he was on.“He felt like someone was controlling him, and he couldn’t be the person he once was.”

Also in the way was a lack of patient-provider racial concordance. “There aren’t many providers who look like us. That was a barrier to treatment, too,” emphasized Middleton.

As a high-performance athlete, A.J. was extraordinarily goal-oriented and pushed to thrive in high-pressure environments. The problem was and is that the stigma against mental health is still very present among coaches and athletes, noted Middleton. “If an athlete pulls a hamstring or breaks their leg, everyone can understand and respect that, but if they say, ‘Hey, I’m having a tough day and wasn’t mentally in it,’ that’s far less understood.”

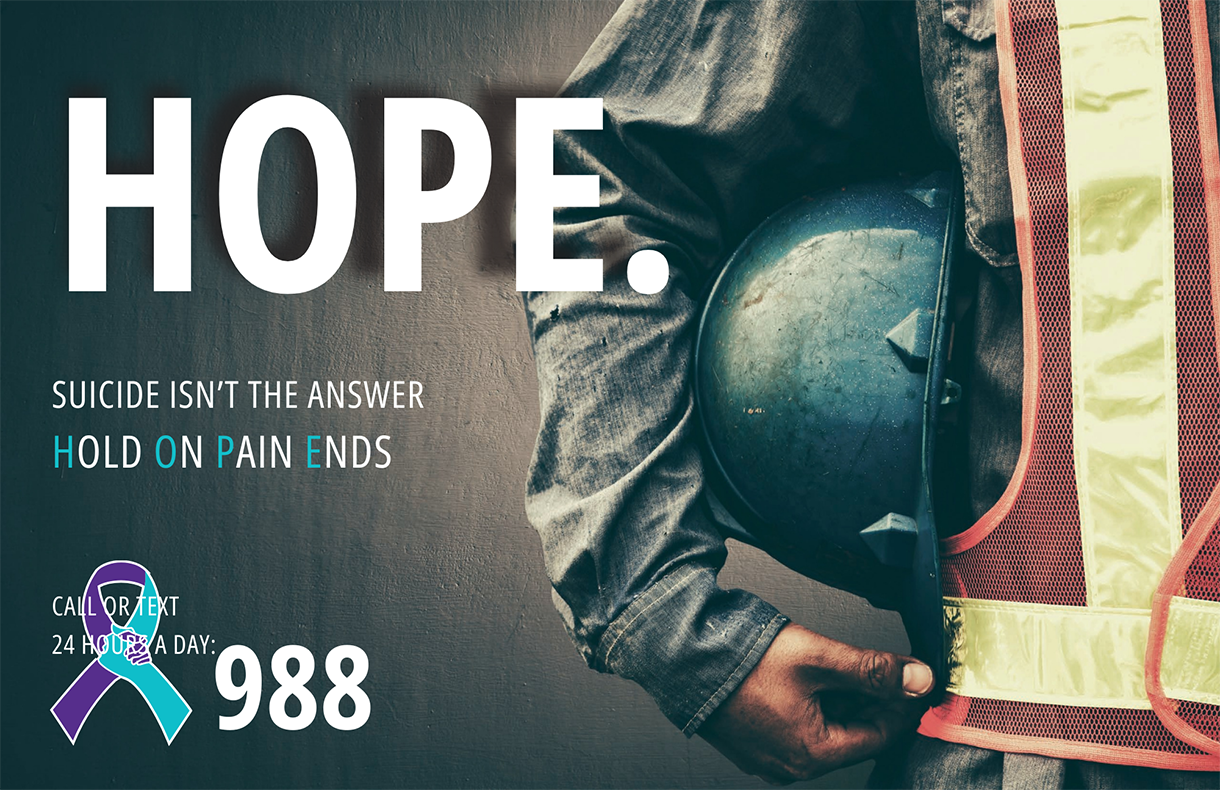

Three months after A.J. died by suicide in 2017, Middleton founded and launched Dream the Impossible in his honor. The nonprofit organization aims to destigmatize mental health and halt and reverse the suicide rate among Black youth and athletes. “So far, we’ve helped over 10,000 young people with mental health education and connection to resources,” he said.

Reaching young athletes is personal. “A.J. was an athlete. I’m an athlete,” said Middleton. The nonprofit—which won the NFL Community MVP in 2017—is working to shift student and professional sports culture toward active listening, trust, and open communication about mental health. “Both student and professional athletes have long had to portray a certain image and maintain a type of perfection that may not reflect how we’re really doing.”

Black athletes face specific challenges, like acclimating to life at predominantly white institutions. “You’re suddenly someplace with people who don’t look like you and might not see life in the same way,” said Middleton. “It takes time to adjust to that.” He’s working to address this issue as the special assistant to the Athletics Department at Appalachian State University, his alma mater and a predominantly white institution where he played safety in college. “It takes student engagement and support, community groups, student-athlete leaders, and counselors,” he said. “There’s a great deal of support here for student-athletes, but we need to continue to grow these resources.”

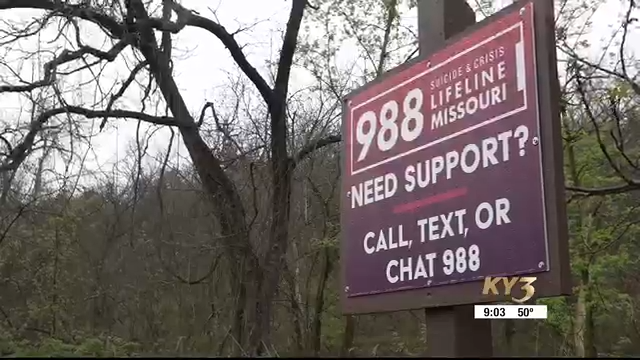

His hope, through Dream the Impossible and in his role at Appalachian State University, is to help young people excel, personally and in their sport. “We want them to find their passion, their purpose, and know how to maneuver through their pain, and connect them to services in the community, if needed.” While Middleton views 988 as a phenomenal resource and an opportunity for crisis care to be more accessible, he emphasizes that there continue to be crisis system barriers, especially for marginalized and small communities. “They often don’t have the resources or budgets for mobile crisis teams,” he said.

Young people today are facing novel challenges, ones that Middleton and A.J. didn’t have to navigate while growing up, like the Covid pandemic and social media. “The pandemic has amplified both the youth mental health crisis and people’s openness to talking about mental health,” said Middleton. According to NCAA student-athlete well-being studies, student-athletes have reported higher levels of anxiety, depression, and mental exhaustion when compared to pre-Covid. The percentage of athletes who self-reported “constantly” or “most every day” mental health challenges were highest among women, Black, Latinx, and other marginalized races and ethnicities, LGBTQ students, and those who reported family economic hardship.

Social media use during the pandemic has created what Middleton calls “the microwave effect,” where student-athletes witness someone else’s rapid ascent in the sports world and assume that’s how it should be. “They expect overnight success because they see other kids getting offers. Instead of moving them to work harder to get there, the comparison makes them sad and less motivated.” He believes social media’s impact has swelled because of the isolation youth experienced during the Covid pandemic. “They’ve been scrolling and accessing so much of this instant success content that young people have overvalued it.”

In 2021, many children and adolescents were also thrust back into in-person school and sports without much, if any, reintroduction, emphasized Middleton. During the pandemic, daily structure fell away for many young people and so too did learning, not only academically but also socially. Public schools (K-12) have reported the pandemic has had lingering adverse effects on students’ socio-emotional and behavioral development. Intermittent Covid-related closures and student and teacher absenteeism have created additional and ongoing barriers to identifying and referring students to mental health services. (Schools are often a primary referral source for mental health services.)

Middleton shares that a critical component of mentoring and coaching kids is getting to know “their baseline.” With so many moments missed during the pandemic, it takes additional awareness and investment to catch up on the struggles students have faced that they didn’t know about, but he’s up to the challenge. “You need to take the time to learn what makes them tick and what makes them anxious and sad,” he said. “They won’t talk to you about everything, but it’s our job to be trustworthy and consistent, so we are there when they need to come to us.”

He taps into A.J.’s story and his own to reach young people who might be struggling. After losing his best friend, Middleton felt tremendous loss and became acutely aware of his own mental health challenges. “I’ve always battled with my mental health, but at the end of the day,” he said, “I’m more aware of how my body and mind operate and what helps me, like yoga, friends, family, peers, and therapists.” He shares with students what’s helped him stay well, including his self-care plan. “It’s better to be proactive than reactive,” he said. “We all handle pain and adversity differently, and we need to have a plan for when challenges arise in our life.”

Photo credit: Miami Dolphins

Source: After Tragedy, Veteran NFL Player Launches Mental Health Awareness Initiative – #CrisisTalk (crisisnow.com)