Twenty-eight years ago, Paolo del Vecchio joined SAMHSA to work in consumer affairs activities. During his tenure, he’s been the director of SAMHSA’s Center for Mental Health Services and the Office of Management, Technology, and Operations. He’s now the director of SAMHSA’s newly established Office of Recovery. “I was the first at the agency to self-identify as a person with a mental health history,” he says.

Historically, mental health crisis care in the United States has left people and family members without choice, making the emergency room the only place to go. In many cases, the experience is traumatizing. “Often people aren’t treated with respect and are subject to restraints and traumatizing procedures,” says del Vecchio. “What I felt from my own experience—and that of many of my peers—is that we need a major whole-scale transformation of how mental health and substance use urgent care is delivered in this country.”

Having experienced crises and the crisis system has made him poignantly aware of what most, if not all, communities lack: recovery-based and trauma-informed crisis care. “I’ve experienced crises from mental health, addictions, and trauma,” he emphasizes. “When in crisis, I’ve been responded to by police officers—restrained and taken in the back of police cars, feeling shame, fear, and pain.”

On March 8, del Vecchio shared on the 988 Crisis Jam one of the worst moments of his life and the shortage of options for care.

…wanting to end my life

without hope, without friends, without a job,

feeling without a future

it was also without choices of where to go for help

The only option was a nearby mental health intake center. When del Vecchio arrived, the first person he saw was a uniformed police officer who told him to take a number. As he waited for hours, he took in the drab, institutional surroundings. Plexiglass separated the staff from everyone else. As he waited, his fears mounted, and he wondered if he’d be restrained again, hospitalized, and given medication he didn’t want. “Would I lose my housing?” he said on the 988 Jam. “Would I lose my family?

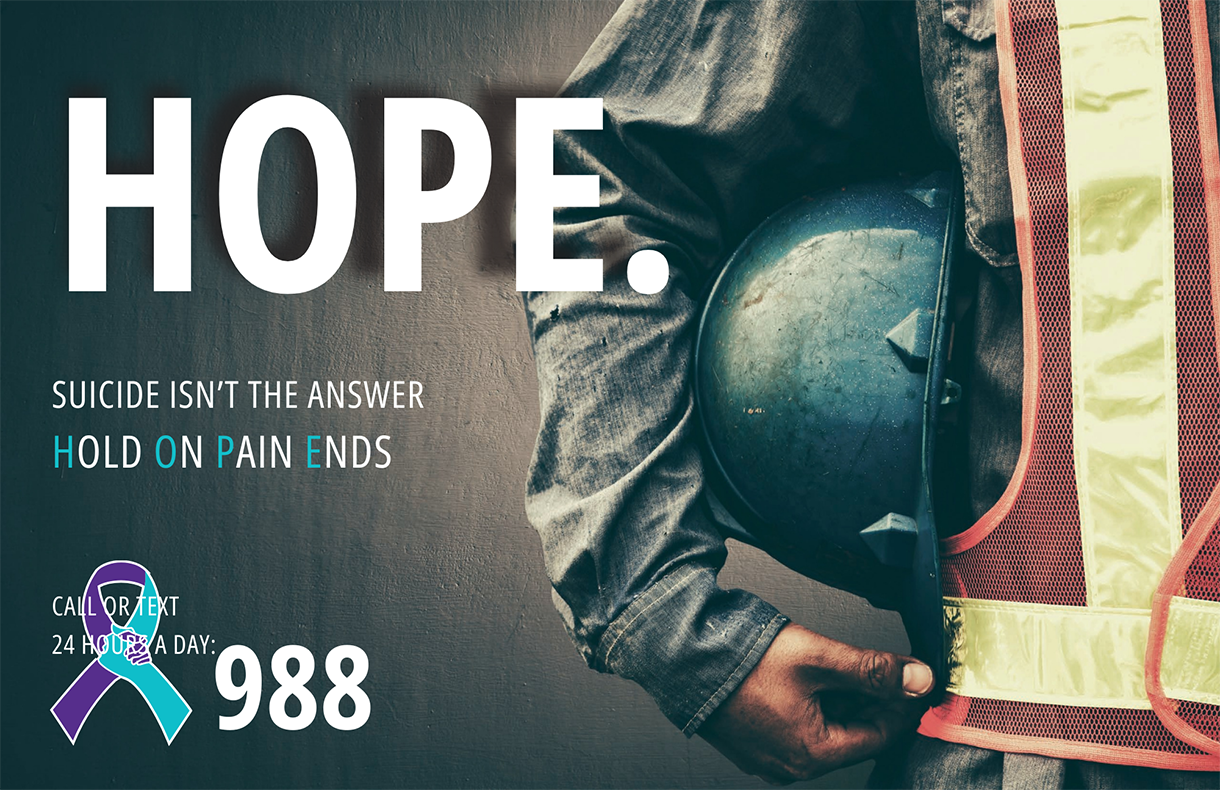

When his number was called, a staff member told him to “return in a month, the soonest there would be an opening.” The center never followed up to check on him. “I left more hopeless than when I came in, and I left through that gray door, never to come back.”

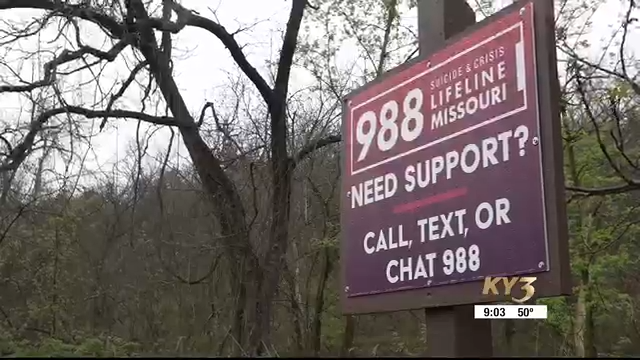

As the Center for Mental Health Services director at SAMHSA, del Vecchio was at “ground zero” for the legislation that became the National Suicide Hotline Designation Act of 2020, a collaborative, bipartisan effort designating 988 as the nationwide telephone number for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (now known as the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline). However, he says 988 offers an opportunity to go beyond a three-digit number and transform the crisis care system meaningfully, “so people receive the care they need.” “Not only short-term but also longer-term recovery supports,” del Vecchio explains.

For example, he highlights how follow-up—after someone has reached out to 988—is vital in crisis prevention. “A simple follow-up phone call to someone presenting in a crisis can be one of the most impactful things we can do to help prevent future crises,” he says.

Dr. Madelyn Gould, a professor of epidemiology in Columbia University’s psychiatry department and a research scientist at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, has evaluated the SAMHSA-funded National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. Her studies have illustrated how vital follow-up is to crisis stabilization, data that influenced many accredited Lifeline call centers to integrate follow-up. “People are still incredibly vulnerable 2-3 weeks after a crisis,” she told #CrisisTalk in 2022.

Megan Stone, manager of Clinical Best Practices and Care Transitions at 988 Lifeline, said that follow-up also allows a person to share more about their challenges. It creates an opportunity for a 988 crisis counselor to fill in any gaps in care between the “initial 988 contact and what happens next.” “…whether that’s getting an appointment with a mental health provider or getting utilities restored,” said Stone.

To maximize the full potential of 988, del Vecchio says legislators, state and federal leaders, and partners must “keep an eye on the prize,” which is a full continuum of recovery-based and trauma-informed care. “That means care that’s person-centered, based on the individual choice of the people who receive care,” he emphasizes. “It’s where people are safe and feel welcomed, their rights are protected, and they have access to a range of care and support to address all of their needs, including peer and family support.” Most of all, del Vecchio says recovery-based and trauma-informed care gives people hope that they can get through a crisis and go on and live a full, happy life.

The Covid pandemic exacerbated mental health challenges among young people in the United States. As the father of three young adults, del Vecchio witnessed his children struggle firsthand. His youngest daughter, now a freshman in college, navigated high school during the pandemic. “It was difficult for her not to be able to interact with peers,” he says. She experienced mental health challenges. He highlights that his daughter isn’t alone. “Young women in the U.S. are experiencing depression and anxiety, often caused by trauma.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) recently released a data summary and trends report, highlighting that female and LGBTQ high school students have experienced high levels of sexual violence, with American Indian or Alaska Native and multiracial high school students experiencing a disproportionate risk.

CDC data has also shown that more young people are presenting to emergency rooms, often because they lack access to other resources in their communities. Emergency room staff are more likely to restrain Black children. Del Vecchio says this highlights the dire need “for equity in healthcare responses and trauma-informed care.”

The pandemic has heightened all stressors on our young people simultaneously, says del Vecchio. “While we are seeing more willingness for people to talk about mental health and addictions, perhaps like never before, we still have a long way to go,” he points out. “Shame, prejudice, and social distancing—from those experiencing challenges—continues to expand.” He sees 988 as an opening to scale evidence-based, holistic care and supports for children, youth, and families.

As states prepare to market 988, del Vecchio suggests they focus on the nexus between storytelling and developing a community safety net, going beyond mental health treatment by addressing quality-of-life challenges and social determinants of health. “We know the reasons why a person presents in crisis is often from social determinants of health—issues from problems with their social supports, housing, or job stress,” he points out.

A robust community safety net can help prevent crises and meet the whole health needs of people in the community. “That’s what a 21st-century crisis care system should look like,” says del Vecchio.

He believes 988 marketing must focus on tailored messaging to ensure it reaches those who need it. “The best people to share messaging about the three-digit number are people within the community,” he says. “Self-disclosure is the most effective way to reduce negative attitudes—what we call stigma.” He notes it’s particularly impactful for those close to the person disclosing, such as a family member, friend, co-worker, neighbor, or faith community member.

“The challenge is how can we share these stories more broadly so people build trust that 988 is an effective resource that can be helpful for people.”

This article was originally published on May 9, 2023.

Source: Paolo del Vecchio Shares His Hopes for 988 – #CrisisTalk (crisisnow.com)